Why I’m Not Paying off My $100,000 Mortgage

At 26 I bought a little condo. I was going to live there five years or something like that.

That’s what most people do. They buy a “starter home” before upgrading to vaulted ceilings, walk-in closets, and double vanities. Why clean one sink when you can clean two?

At some point I decided more doesn’t mean better. That 1,000 square feet is good enough, and because I’ve lived here forever people ask me if it’s paid off. I don’t care if they know or not, so I tell them I owe $100,000.

“You should pay it off.”

“Why?”

“Peace of mind.”

This question — should you pay off your mortgage — is one of those debates where I’m not going to tell you what to do, but I’ll tell you how I think about it. Where is the best place to put your money: in a house, or investments?

And before you tell me your house is an investment, I’m going to tell you it’s not.

Using Robert Shiller’s data I calculated the inflation-adjusted return on housing from 1890 through 2016 was 0.39%. Over the same time period the S&P 500 returned 6.48%.

A 6% difference didn’t seem right so I asked Shiller and he told me:

“Yes, that is more or less right, in the past century or so. Land is getting more scarce, but the cost of construction is going down (due to mass production, etc.). Land is not a big component of home value in most places.”

If we know that a house isn’t the best investment, what’s the rush in paying it off? Let’s take a look at your two options.

Option #1: Extra mortgage payments

I always recommend doing whatever has the higher number. If you’re deciding between paying off debt, like a mortgage at 4%, or investing and getting a return of 7%, the better financial decision is invest.

Then some guy comes along and says that’s bad advice. Literally.

“This bad advice. Good advice would be saying: you are guaranteed a X% return if you pay down your debt.

You CANNOT say you are guaranteed a 7% return by investing in the stock market. Just because the average is 7% does NOT mean it will go up (at all) 7% on average for X number of years. We very could easily have a few down years where you will lose money while the loan accrues more interest. You could put your upper body in the oven and your lower body in the freezer and your body temp would be average but you wouldn’t be in very shape now would you. Merely citing an average is intellectually lazy..

Overall bad advice and bad post.”

The problem with this? The “known unknowns”. What if you lose your job, your spouse leaves you, they make changes to Social Security. And all your extra money went into the house.

Which reminds me of a story. A couple was living in a $500,000 house and putting all their extra money into additional mortgage payments. The guy would brag, “Where else can you earn a guaranteed 4%?”

One day, on his way to work, he got into a terrible car accident. He lived, but was in the hospital for months. Had permanent brain damage.

After he stopped getting paychecks they couldn’t make their mortgage payment. Did the bank care they made all those extra payments the past seven years? No, they just wanted their monthly check. They foreclosed.

If they had been putting their extra money into a savings or investment account they could have kept making payments, buying some time to sell the house.

Instead, they lost everything.

Option #2: Keep mortgaging

Conventional wisdom is to pay off debt, but rich people don’t get rich by following conventional wisdom they get rich by investing.

Look, a 30-year fixed mortgage is pretty cheap at 4%, and over the next 30 years it’s likely the market returns more than 4%.

Saying that isn’t “intellectually lazy”. It’s what happened in the past, and you have to figure the future won’t be significantly different.

Since 1926 the average return of the S&P 500 for all 30-year periods was about 10%, with the worst being 8%.

Think about that. Even the worst return is 4% higher than a mortgage. If that makes sense, it makes sense to always be borrowing the cheapest money you can for the longest term.

How do you do this? Well, you use what’s called a cash-out refinance.

Say you own your house worth $225,000. You cash out $180,000 (leaving 20% equity), and refinance $180,000 with a 30-year mortgage at 4%.

The payment for a $180,000 mortgage is $860 a month, or $10,312 a year. If you’re living off investments and using the 4% rule you need $250,000 to support that ($10,000 x 25).

Here’s another way to say that. You only need $70,000 extra in your portfolio. You cash out $180,000, invest it, and need an additional $70,000.

But wait, there’s more.

The 4% rule increases the annual withdrawal by inflation, but payments for a fixed mortgage are just that, fixed.

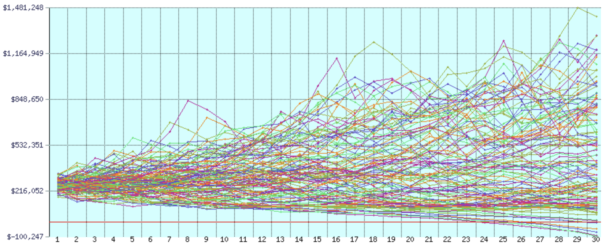

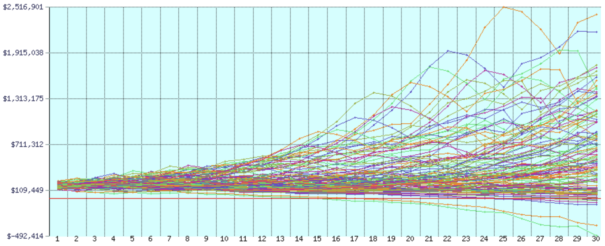

You can go to FIRECalc, a retirement calculator, and put in $10,000 spending and a $250,000 portfolio. That gives a 95% success rate.

But remember, the 4% rule is increasing the $10,000 withdrawal by inflation, so what happens if you set the inflation rate to 0%?

It turns out that a portfolio of $170,000 has the same 95% success rate. Meaning, you only need $170,000 to make the $860 a month mortgage payment. That’s $10,000 less than you cashed out. Make sense?

Look at the results. You start with $170,000, withdraw $10,000 every year for 30 years, and end up with an average balance at the end of $587,514.

In theory, you get half a million plus a paid-off house.

What should you do?

It seems that always having a cheap mortgage is the way to go. You have more money invested in the market, money that’s getting a better return.

The downside? Never owning your home. Some people want that peace of mind, others want more money. There’s no right decision, only decisions with different benefits.

I’m still sitting here making mortgage payments. Some day I might do a cash-out refinance or buy a new house with a 30-year mortgage, but I don’t have to make that decision today.

That’s fine, because what’s important is getting clear on what decision you’re making, and what you’re giving up by making that decision.

This is personal finance, which is a lot like life, you make tradeoffs.