The American Dream Is a Financial Nightmare

The year was 2001, I was 21-years-old, with one semester of college left. I wasn’t taking school very serious anymore, so me and my roommate we were going through cases of Natural Light beer every week. While I was having fun celebrating the last days of fraternity life, I was also looking forward to the next stage of my life – a nine to five job I had accepted in Madison, Wisconsin.

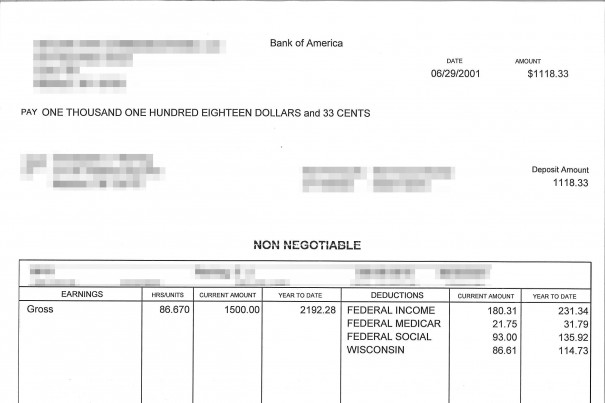

After graduation I made the move from Illinois, settling into a run-down studio apartment in a seedy neighborhood. It was cheap at $425 a month, but I was so broke I had to borrow the security deposit and first month’s rent from my mom. Nevertheless, I was excited because I’d finally be making adult money; here’s my very first paycheck:

With good money coming in, I decided to buy a new car because I was embarrassed to pick up dates in my 13-year-old Chevy Celebrity that was rusting everywhere. Looking back, I realize I was following the life script that was ingrained in me: get a college degree, land a nine to five job, and buy a new car.

One year later my apartment lease was up, but I chose to renew even though my finances had stabilized and I could afford a nicer place (people were smoking marijuana and playing dice in the hallways). The following year I found a better job, and moved downtown to an upscale 650-square-foot apartment with a lake view.

But a swanky apartment wasn’t enough; to show everyone I was successfully navigating adulthood, and to keep on track, I needed to buy a house. So I saved for a down payment, creating automatic monthly transfers of $1,000 from my checking account to an online savings account. That put the money out of reach so I couldn’t spend it. Three years later I had saved $40,000, enough for a 20 percent down payment on a $200,000 house.

It’s now 2006, and I was 26-years-old, ready to achieve the American Dream of buying a house. I signed over all my hard-earned money, and that was probably the worst financial decision I’ve ever made.

Recently, many people have emailed to say, “I finally have enough money to buy a house,” or “I’ve lived in an apartment for 10 years, it’s time for me to buy.” Like those people, and probably you too, I thought I was making the best decision to buy, but I hadn’t done any homework, or the math.

I naively believed:

- Renting is just throwing money away

- A house always appreciates in value, so it’s one of the best investments for the money

It was my own fault for not becoming an informed buyer, but I also felt the social pressure:

- Buying is the next step in the life script, after a college degree, a nine to five job, and a new car

- Our parents tell us we should be buying

- Our friends are buying, and they’re asking us when we’re going to

As it turns out, what I believed about buying was flat-out wrong, and because I didn’t do the math for the biggest financial decision of my life, I’ll eventually realize two losses – the property selling for less than what I paid, and the potential profit from putting the $40,000 to work for me.

Belief #1: Renting is throwing money away

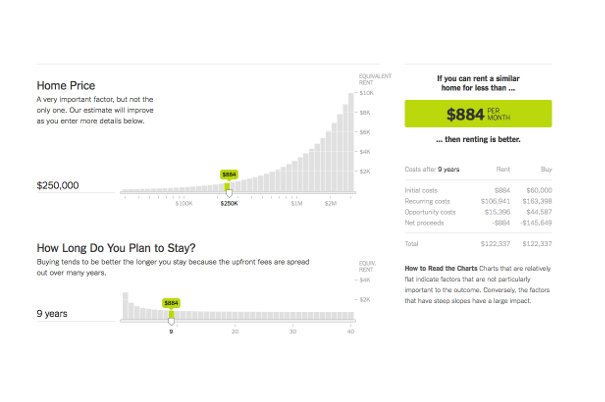

The Times has a beautiful calculator to help determine if it’s a better financial choice to rent or buy, and I think it’s a great litmus test to steer you in the right direction.

But the issue I have with that calculator is it doesn’t factor in the soft costs of owning a house:

- Your time. Just like money, time is a resource, and you’ll spend it: researching problems with your appliances, calling electricians and plumbers, and then waiting around for them, fixing small issues with hand tools, taking trips to the home improvement store, mowing the lawn, removing snow, etc.

If we reasonably assume our time is worth $20 an hour, and we’ll spend 8 hours a month on those things, that’s $2,000 a year in labor that renters save.

- Reduced flexibility. It’s way more difficult to move for a better job, and that job could be across town – a longer commute you don’t want – or in a different city. Either way, you won’t make the best decision for your career because you become financially, and emotionally, tied to your house.

Plus, with a house you’re still throwing money away; keep your checkbook open for property taxes, homeowner association fees, maintenance, replacing things when they break, and then break again, replacing the roof, and keeping it up-to-date. You can figure to spend up to 50% of your mortgage payment on those things.

Belief #2: A house is the best investment

Historically, it’s a bad one.

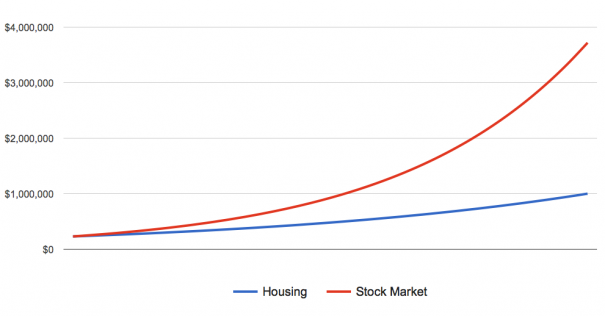

The mistake people make is when they hear someone say, “I bought my house in 1987 for $230,000, and today it’s worth $1 million,” and then think a profit of $770,000 over 28 years sounds pretty good.

But if we calculate the compound annual growth rate over that timeframe it’s 5.39 percent. The stock market – the S&P 500 – returned 10.45 percent. Here’s what that 28-year difference looks like:

Housing has always had a terrible track record as an investment – from 1890 to 2012, the inflation-adjusted return (i.e. taking inflation out) on residential real estate was 0.17 percent. That means a house purchased for $5,000 in 1890 would be worth $6,150 in 2012.

Over the same time period the stock market returned an inflation-adjusted 6.27 percent. That means a $5,000 investment in the market would be worth over $8 million. That’s called the opportunity cost – when you choose to use your money one way, rather than another.